History never repeats

I tell myself before I go to sleep...

Neil Finn wrote these words in 1981 on that great album Waiata, which I have recently rediscovered. Aptly the B side was “Holy Smoke”.

So, what has this got to do with ParkScience and the weird and wonderful world of parking you ask. It had me thinking about my early days in parking, moving to Sydney in the heady days of 1988 before FBT, Parking Levies and mobile phones.

The parking market was exceedingly robust and the challenge (it seemed) was to get hold of as many leased sites as possible on the longest terms as possible, then turn up the dial.

My first task was to look at the history of (like for like) parking rates over the previous ten years in Sydney. I found they had grown at an AVERAGE of 13% year on year over the ten years! No hiccups, just a nice line reaching skywards on the graph. As rents had been increasing by around four percent – or by some exotic formula Laurie Wilson devised based on parts of a rate structure that was very clever if you knew how it really worked – the industry was making very good profits.

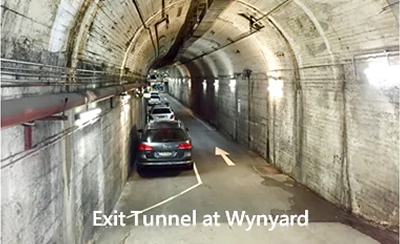

This reinforced the very aggressive bidding that Wilson (and to a lesser extent Kings and Secure) had commenced, with the now infamous Wynyard Carpark having been won six months before I moved over from the wild West.

We had seen a decade of 13% compounding revenue growth – why would it stop? The whole market was engaged in a bidding war. If revenues are growing by 13% - you can easily afford rent increases of 5% - and eventually landlords were demanding 7% rent growth on 10-year fixed term agreements, with further ten year options.

For those born before 1970 and learned math longhand will know the “Rule of Seventy Two”.You divide seventy two by the compounding increase to arrive at the number of years it will take to double. At 7% compounding, the rent will double by year ten. So, a $2,000,000 rent becomes $4,000,000.

Prior to the untimely end, Wilson had four substantial offers in the market where the business case was to lose over $1,000,000 each in their first year of operation. Wynyard was already losing over $1,000,000 by 1989.

So, what went wrong? Was it a “Black Swan” event – or a “Perfect Storm”?

Neither of the above (and maybe it was because these terms had not been invented yet) – it was the economy, which is not as predictable as fixed rental increases. Keating engineered the recession we had to have -the RBA cash rate hit 17.5%, unemployment went over 10% as interest rates were used to curb inflation – which went over 8% before falling to 2% by 1993. The State Bank of VIC & SA both collapsed plus Pyramid Building Society (aptly named) and a raft of others.

Office vacancies lagged by a few years (due to office developments that commenced during 1990/91 taking a few years to complete) and Melbourne peaked at over 30%, Perth over 25% and Sydney at 20% through 1993.

There were fewer bottoms on seats and those who still had a job were paying mortgage rates up to 18%. Parking customers quickly became public transport users, revenues declined but rents continued to rise. And millenials think we were the lucky generation.

And the key to this was the various revenue streams (casual/early bird night/weekend and monthlies) were essentially short term. So there was a mismatch between long term rental obligations to landlords and the short-term promise of income from customers.

Kings and Hooker parking disappeared. Laurie Wilson lost control of his business, a large part of which was sold to the Kwok family of Hong Kong.

You are probably reading this thinking – how could anyone (let alone entire industries, including banking and commercial property) together with parking operators have got it so wrong?

The upshot for parking operators was no more 10 year straight deals or 7% increases (or both) – or CPI plus 1% and instead shorter leases with fixed 3% increases and lease clauses that mitigated the risk of large tenants leaving. And even fixed 3% increases are now being looked at as revenues across a large number of sites has flattened out following substantial upward movement in hourly rates in most capital cities over the past five years. $25 per hour to park in Brisbane is not cheap.

I am not a financial analyst, but there is a strong argument we are seeing similar patterns in some markets at the moment. Companies losing substantial sums each year (Uber/Lyft) on the basis of growing revenue and market share or “disruption” of legacy providers with profits forecast at some distant point in the future.

In particular We Work appears to exhibit many of the same attributes of the operators in the 80’s – focussing on market share and growing the size of the business above profit with the same mis match between the long-term rentals and their far shorter-term revenue streams. It currently has offices in around 100 cities across the globe totalling over 1.4 million square meters.

Michael Gross, the company’s vice chairman recently said “Were looking at building this business out, not just maximising profitability over the next one to two years”.

We Work is essentially a business of leasing (or owning) offices, using modern design for upgrades, and breaking the space into small lots that rent out at far higher rate than the same floor let as a whole.

We Works losses more than doubled last year to about $1.9 billion,even as its revenue doubled to $1.8 billion. It has $6.6 billion in cash and committed capital.

We Work issued $US702m of 7.875% coupon bonds in April 2018 with a face value of $100. They traded as low as 0.86 cents in January 2019 after reports surfaced that SoftBank (major investor) planned to dial back its investment. They are currently trading around 0.92 cents – showing a 9.59% yield. Clearly not all bond traders are convinced with the growth strategy at the moment.

And there is no shortage of competitors for We Work – or barriers to entry to the market, which we see in Australia with the large REITS developing their own short-term flexible, office products – such as DEXUS Place.

The last words belong to Neil Finn.

“And there's a light shining in the dark

Leading me on towards a change of heart, ah”